The Deeper Dimensions of Breath: Smoothness, Rhythm, Depth, and Ratios

In previous parts of this series, we explored how breath location (diaphragmatic vs. chest breathing) and pace (breaths per minute) are core components of breath’s qualities in relation to health.

In this final part, we turn to some of the less talked about yet equally powerful characteristics that shape our breath. These subtle elements are now increasingly studied in modern science. Together, we will explore how they can enhance your ability to regulate your inner state by affecting your physiology, emotion, and cognition.

Beyond Pace and Place: The Other Key Characteristics of Breath

Dr. Alan Watkins, a physician, neuroscientist, and international expert on leadership and human performance, has done extensive work on breathing as a foundation for emotional intelligence and human thriving. He has identified several key variables that shape your breathing and your internal state. Among the most influential are:

- Smoothness – how even and continuous the breath is (no jerks or gasps)

- Regularity – the consistency of rhythm over time

- Depth – how deeply you breathe (shallow vs. deep)

- Ratios – the timing between inhale and exhale

- Pauses – breath retention after inhalation or exhalation

These elements work together to shape how the breath influences your physiological and emotional state. Let’s explore each —starting with two of the most overlooked: smoothness and regularity.

A smooth, regular breath: The Hidden Key to Coherence

Among the many variables that influence breathing, smoothness and regularity may be the most overlooked — yet most essential — for achieving physiological coherence: a state of optimal functioning in which different systems of the body, including the heart, brain, and breath, are synchronized and working in harmony.

What Does the Science Say?

Most research in the fields of HRV biofeedback, paced breathing, and respiratory physiology focuses on measurable parameters such as breath rate, inhale-to-exhale ratio, or breathing location (diaphragmatic vs. thoracic). While smoothness and regularity are often implicitly encouraged, they remain qualitatively described rather than quantitatively assessed. In other words, they are felt and taught, but rarely measured.

There is also no standardized definition of what constitutes “smooth” breathing in the scientific literature. However, smooth breath is generally characterized by:

- Gentle, gradual transitions between inhale and exhale

- No abrupt pauses or jerky shifts (unless intentionally introduced)

- A steady, wave-like quality, like the rising and falling of a calm tide

It’s not just about slowing the breath down. When breathing at your resonant frequency (~0.1 Hz, or about 6 breaths per minute), adopting this effortless, wave-like quality supports synchronized, in-phase oscillations in respiration, blood pressure, and heart rate. As these rhythms synchronize and amplify, heart rate variability (HRV) increases and baroreflex sensitivity is enhanced (Sevoz-Couche et al., 2022).

This coherent physiological state is more than just a biomarker: it’s linked to improved emotional regulation, stress resilience, physical health, and cognitive performance (Lehrer et al., 2020).

What disrupts smooth and regular breathing?

The lack of fluidity and regularity in the breath can arise for various reasons, depending on the context. Here are some common contributors:

- Tension in the respiratory muscles: Tightness in the diaphragm, intercostals, jaw, or throat can restrict airflow and make the breath feel strained or jerky.

- Over-focusing or effortful breathing: Trying too hard to “control” the breath can introduce subtle muscular tension, breaking the natural rhythm. That’s why finding a soft, effortless quality is essential.

- Mild breathing dysregulation: Elevated stress or sympathetic nervous system activity can lead to shallow, irregular, or erratic breathing patterns.

- Habitual breath-holding or breath stacking: Without realizing it, many people pause between breaths or take new inhales without fully exhaling the previous one. This pattern — called breath stacking — can lead to a buildup of tension and disrupt the breath’s natural flow.

The quality of the breath reflects the quality of the mind

In yoga and meditation traditions, smoothness is often taught as an embodied quality of awareness. At Zuna Yoga, we like to say, “Let the breath move like the tide of a peaceful ocean”. This isn’t just poetic — it reflects a ideal physiological state. A smooth, continuous breath stabilizes the oscillations of the nervous system, reduces the “noise” of stress, and allows the mind to settle into deeper states of presence.

Paying attention to the texture of the breath is essential: Is the breath smooth? Does it flow effortlessly? Or does it catch, strain, or stutter?

A smooth, rhythmic breath can become a meditation in itself. Think of it like driving: a smooth, even ride feels very different from a jerky, stop-and-start journey. It’s no coincidence that many people report falling into a meditative state while driving on a quiet highway: smoothness and rhythm matter. These qualities offer a path inward, a way to attune to the deeper, subtler rhythms of life.

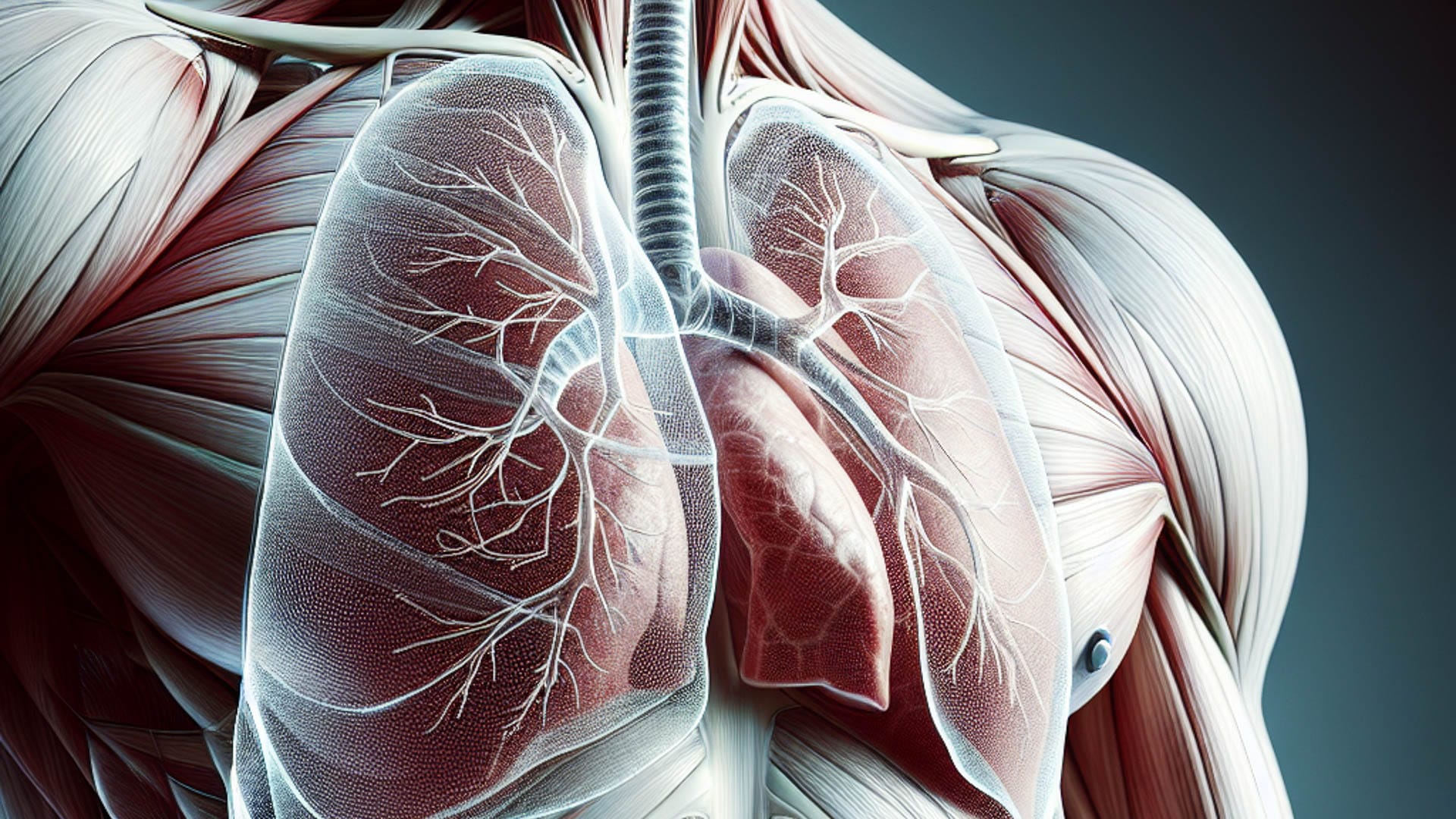

Breath Volume: The Balance Between Depth and Rate

As we slow the breath, it’s natural to slightly increase the depth of each breath in order to maintain the same minute ventilation: the total volume of air breathed per minute. This relationship is captured by a simple equation:

VE = VT × RR

VE (Minute Ventilation): Total volume of air breathed per minute

VT (Tidal Volume): Volume of air taken in during a single, normal breath

RR (Respiratory Rate): Number of breaths taken per minute

For example, if we normally breathe 12 times per minute with a tidal volume of 500 mL, our minute ventilation is: 12 breaths/min × 500 mL = 6 liters per minute (L/min)

If we slow the breath to 6 breaths per minute, we would need to double the tidal volume to maintain the same minute ventilation: 6 breaths/min × 1000 mL = 6 L/min. This demonstrates how slowing the breath naturally calls for increased depth.

But again, the smooth and gentle quality of the breath is essential. If we slow the breathing rate to 6 breaths per minute but breathe too deeply or forcefully — say, with a tidal volume of 2000 mL — our minute ventilation rises to: 6 breaths/min × 2000 mL = 12 L/min. This results in over-ventilation or “overwashing” of carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the body, even though the breath rate is slow. This is a form of hyperventilation, which doesn’t only occur when we breathe too fast, but also when we breathe too deeply, taking in more air than the body’s metabolic needs require.

That’s why depth must be balanced with softness and control. A full breath doesn’t mean a forced breath. Ideally, depth arises naturally, as the body adapts to a slower pace and greater awareness. The goal is not to force large breaths, but to cultivate a full yet smooth, steady, and relaxed rhythm that meets the body’s needs without strain or excess.

The Power of Ratios: Inhale, Exhale, and the Space Between

Breathing ratios — that is, specific timings of inhale, exhale, and breath holds — are commonly used to regulate energy, balance the nervous system, and deepen awareness. These ratios can be found in ancient yogic pranayama techniques, meditation practices, as well as in modern therapeutic approaches, breathwork modalities, and stress management methods.

Some of the most commonly used breathing ratios include:

- 1:1 → Equal-length inhale and exhale (balancing)

- 4:6 → Inhale for 4 counts, exhale for 6 (emphasizing parasympathetic activation)

- 4:4:4:4 (Box breathing) → Inhale, hold, exhale, hold for equal counts (used in military and therapeutic contexts)

- 1:4:2 → Inhale for 1 count, hold for 4, exhale for 2 (a classical pranayama pattern to develop kumbhaka)

- 4-7-8 → Inhale for 4 counts, hold for 7, exhale for 8 (popularized by Dr. Andrew Weil)

While the techniques vary, all these breathing ratios aim to balance the autonomic nervous system—promoting relaxation, improving mood, and reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression. Emerging scientific research supports these benefits (Fincham et al., 2023; Bentley et al., 2023), though more rigorous studies are still needed.

Are All Breathing ratios Equally Effective?

In Part 2 of this series, we explored how slow-paced breathing, especially at a steady rhythm of about 6 breaths per minute, supports vagal activation and autonomic balance. But that raises a question:

Are the benefits of breathing ratios simply due to slower breathing, regardless of the pattern? Slowing the breath is indeed a key mechanism—but some patterns may be more effective than others.

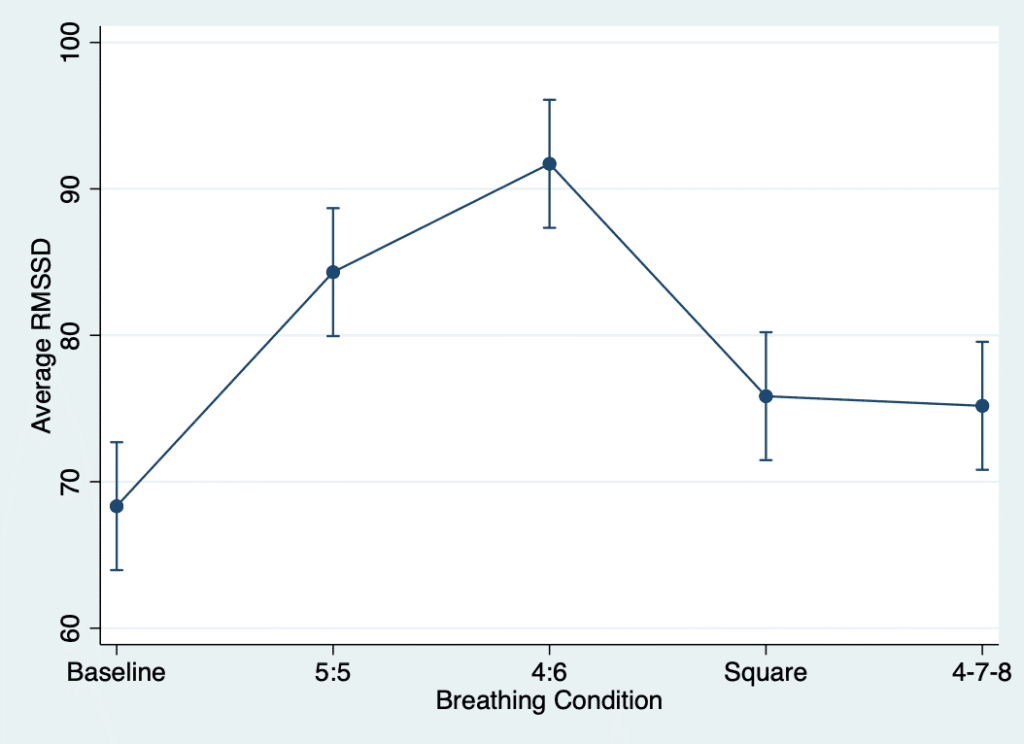

This was precisely the question explored by a research team at Brigham Young University (Marchant et al., 2025). They compared box breathing and 4-7-8 breathing with resonance breathing at 6 breaths per minute, using either a 5:5 ratio (equal inhale and exhale) or a 4:6 ratio (longer exhale). Participants practiced each technique for 10 minutes (5 minutes of instruction, followed by 5 minutes of physiological measurement), and the effect of each pattern on heart rate variability (HRV), blood pressure, mood, and carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels was evaluated.

Key Findings

The study from Marchant et al., (2025) found that breathing at 6 breaths per minute led to greater increases in HRV compared to box breathing and 4-7-8 breathing. While blood pressure and mood improvements were observed across all techniques, results were inconsistent. Interestingly, the 4:6 ratio slightly outperformed the 5:5 ratio for HRV, although the difference wasn’t statistically significant. This aligns with established physiology: inhalation stimulates the sympathetic system, while exhalation enhances parasympathetic activity. Longer exhale will help to slow the heart rate and promote relaxation. Prior research also shows that longer exhalations are linked to higher HRV, reflecting stronger vagal tone (Laborde et al., 2021; Van Diest et al., 2014; Strauss-Blasche et al., 2000; Bae et al., 2021).

Interestingly, while nearly 90% of participants could maintain the 6-breaths-per-minute rhythm, only 74% managed to accurately perform the more complex box and 4-7-8 patterns. This is likely due to their slower pacing (around 3–3.75 bpm), which requires greater control and tolerance for breath holds. Without prior training, these patterns may feel uncomfortable or subtly activate the stress response —possibly explaining their lower HRV effect in this study.

Average Heart Rate Variability (measured as RMSSD Scores) Across Different Breathing Conditions (Original Units) with Standard Error Bars. Reproduced from Marchant et al. (2025), under CC BY 4.0.

So… Is 4:6 the Best Ratio?

For beginners, probably — it’s simple, calming, and accessible. However, it would be valuable to repeat Marchant et al. study with experienced practitioners, who may benefit more from slower or more advanced breath ratios after adequate training. In essence, all breathing patterns can be powerful, but the most effective ratio depends on the individual’s experience, physiology, and comfort level.

A Note on Breath Holds & Preventing Hyperventilation

Slowing the breath continuously, without any breath holds, can unintentionally lead participants to breathe more deeply or forcefully in an attempt to “fill” the longer breath cycle. This increases ventilation and leads to greater carbon dioxide (CO₂) loss through exhalation, potentially triggering that hyperventilation phenomenon we talked about earlier.

In this context, Marchant et al. (2025) study found that participants breathing at 6 breaths per minute without breath holds showed a reduction in PETCO₂ (end-tidal carbon dioxide, a key marker of CO₂ levels in the body). This effect was not observed in the slower breathing patterns such as box breathing and 4-7-8 breathing, which both include breath retention after inhalation and/or exhalation.

The key distinction lies in the structure of the breath cycle: Breath holds in patterns like box and 4-7-8 breathing allow CO₂ to accumulate in the lungs and bloodstream during pauses, reducing the net loss of CO₂ through exhalation. In contrast, continuous slow breathing can lead to CO₂ washout, even if the breathing rate is slow.

How Breath Holds Influence Autonomic Balance

A study by Laborde et al. (2021) investigated whether adding brief respiratory pauses (0.4 seconds) after inhalation or exhalation during slow-paced breathing (SPB) would enhance cardiac vagal activity — a measure of parasympathetic engagement. The results showed no significant additional benefit.

However, pause duration may play a critical role and a very short pauses of less than 1 second may be too brief to meaningfully impact autonomic tone. In a separate study by Russell et al. (2017), researchers examined the effects of adding a longer post-exhalation rest period (>1 second) to a slow-paced breathing pattern. They compared a 4-2-4 pattern (inhale for 4 seconds, exhale for 2, rest for 4) with a 5-5 pattern (inhale and exhale with no pause). The findings revealed that:

- The 4-2-4 pattern produced greater increases in high-frequency HRV (HF-HRV), a marker of parasympathetic (vagal) tone.

- Participants reported the 4-2-4 pattern felt easier and more relaxing, likely due to the built-in pause, which prevented over-breathing and offered a gentler rhythm for the nervous system to settle into.

These results suggest that pauses, particularly after the exhale, may enhance relaxation and vagal engagement. That said, the “dose” is important: pauses that are too short will have little effect, while pauses that are too long can lead to gasping or disrupt the natural, soothing flow of breath.

At Zuna Yoga, we like to say that pauses should be just long enough to feel the completion of the breath, rather than interrupt its natural rhythm. These pauses are not breaks in the action, but rather elegant, smooth transitions, a subtle space where one wave ends and the next begins. When done skillfully, they soften the edges of the breath and deepen the meditative quality of each cycle.

Bridging the Breath’s Key Features: The Zuna Yoga® AgniRaj Method

As explored in Parts 1, 2, and 3 of this blog series, modern science highlights several essential elements of breath quality — pace, location, smoothness, rhythm, volume, and ratio — as central to our ability to regulate physiological, emotional, and cognitive states.

These elements are elegantly woven and deeply interrelated in Zuna Yoga®’s signature breathing method: AgniRaj.

What is AgniRaj?

AgniRaj is a full-body breath, rising from the pelvic floor to the collarbones. It integrates classical yogic wisdom with modern somatic science to create a powerful method for deep inner regulation and energetic embodiment.

Key features of AgniRaj Breath

- A slow, rhythmic pace, with the breath filling the body like water pouring into a glass — from the bottom up. Because most of us were never taught how to breathe optimally, students are guided step by step into a deeper, more embodied breathing experience. A metronome supports this process by creating a steady rhythm. We typically begin with a 6:6 ratio (inhale:exhale), around 5 breaths per minute, and progressively train the body to relax into slower rhythms. Within a few weeks, many students access deeper states by learning to breathe effortlessly at a 9:3:9:3 ratio (inhale:pause:exhale:pause), approximately 3 breaths per minute.

- Smoothness in the breath and the transitions, free of jerky stops or tension. Verbal and somatic cues help create this ocean-like wave in the breath, inviting grace and fluidity in each cycle.

- Full breath, with strong emphasis on abdominal breathing to stimulate the vagus nerve and promote parasympathetic activation.

- Pelvic floor engagement, in sync with the diaphragm’s upward movement. This coordination helps stabilize the trunk, supports spinal alignment, and enhances breathing efficiency and relaxation.

- Physical awareness, using the spine and deep core as anatomical anchors. Fostering healthy postural alignment supports optimal use of lung volume and diaphragm movement, while helping to prevent dysfunctional breathing patterns that arise from overusing accessory muscles in the neck and chest.

- Energetic awareness, feeling the breath not only as a physical movement, but as a wave of life force energy. This attunement cultivates a meditative state of internal listening, deepening presence and integration.

How to Practice AgniRaj

Inhale:

- Begin by drawing the breath deep into the pelvic region.

- Allow the breath to rise through the navel, lower ribs, and up to the collarbones.

- Imagine the inhale like water filling a glass from the bottom up, creating a sense of internal lift and space along the spine

Exhale:

- Gently engage the pelvic floor and lower abdominals to initiate the exhale

- Let the breath leave the body in an upward wave, maintaining gentle lift through the rib cage

- Keep the spine long and supported, allowing the exhale to stabilize the core and guide awareness inward

Rather than isolating individual elements of the breath, the AgniRaj method integrates all its key dimensions into a cohesive and embodied practice. It serves as a somatic anchor for presence and a powerful tool for nervous system regulation — a living expression of what it means to breathe consciously, intentionally, and soulfully.

Conclusion

In this final part of the series “Breath Awareness in Yoga”, we’ve moved beyond the basics of breath rate and location to explore the subtle yet powerful dimensions of smoothness, rhythm, depth, and ratios. Long embedded in ancient yogic traditions and now increasingly supported by modern science, these elements offer tools not only for regulating physiology, but for transforming inner experience.

The AgniRaj method offers a practical and soulful framework for exploring these dimensions. When approached with awareness and intention, it becomes more than a breathing technique — it becomes a mirror of the mind, a regulator of emotion, and a gateway to presence.

We hope this series has supported you — whether you’re refining your breath for well-being, meditation, or performance. Keep breathing, explore AgniRaj, and may this journey continue to guide you into the deeper layers of breath, revealing new states of calm, clarity, and embodiment.

References

Bae, D., Matthews, J. J. L., Chen, J. J., & Mah, L. (2021). Increased exhalation to inhalation ratio during breathing enhances high-frequency heart rate variability in healthy adults. Psychophysiology, 58, e13905. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13905

Bentley, T. G. K., D’Andrea-Penna, G., Rakic, M., Arce, N., LaFaille, M., Berman, R., Cooley, K., & Sprimont, P. (2023). Breathing practices for stress and anxiety reduction: Conceptual framework of implementation guidelines based on a systematic review of the published literature. Brain Sciences, 13(12), 1612. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13121612

Fincham, G. W., Strauss, C., Montero-Marin, J., et al. (2023). Effect of breathwork on stress and mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised-controlled trials. Scientific Reports, 13, 432. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27247-y

Laborde, S., Iskra, M., Zammit, N., Borges, U., You, M., Sevoz-Couche, C., & Dosseville, F. (2021). Slow-paced breathing: Influence of inhalation/exhalation ratio and of respiratory pauses on cardiac vagal activity. Sustainability, 13(14), 7775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147775

Lehrer, P., Kaur, K., Sharma, A., Shah, K., Huseby, R., Bhavsar, J., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Heart rate variability biofeedback improves emotional and physical health and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 45, 109–129.

Marchant, J., Khazan, I., Cressman, M., & Steffen, P. (2025). Comparing the effects of square, 4–7–8, and 6 breaths-per-minute breathing conditions on heart rate variability, CO₂ levels, and mood. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 1–16.

Russell, M. E., Scott, A. B., Boggero, I. A., & Carlson, C. R. (2017). Inclusion of a rest period in diaphragmatic breathing increases high frequency heart rate variability: Implications for behavioral therapy. Psychophysiology, 54(3), 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12791

Sevoz-Couche, C., & Laborde, S. (2022). Heart rate variability and slow-paced breathing: When coherence meets resonance. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 135, 104576.

Strauss-Blasche, G., Moser, M., Voica, M., McLeod, D. R., Klammer, N., & Marktl, W. (2000). Relative timing of inspiration and expiration affects respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology, 27(7), 601–606.

Van Diest, I., Verstappen, K., Aubert, A. E., Widjaja, D., Vansteenwegen, D., & Vlemincx, E. (2014). Inhalation/exhalation ratio modulates the effect of slow breathing on heart rate variability and relaxation. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 39(3–4), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-014-9253-x